The conversation drifting in from the other room is like nothing I have ever heard. A woman's laughter and a man's grunts are interspersed with repetitive numbers and questioning guesses at letters and words. "Three? H? One? A? Happy? No? Half? Half of? Half of it?"

The woman is Stephanie Sharpe, a homecare worker and friend of mine who has agreed to take me along to meet and photograph Beany, one of the people with whom she spends her weekdays. She has talked about him before, and the incredible affect he has had on her but, at this point, I really have no idea what to expect. I'm sitting on a couch, placed far out of my comfort zone.

"All right," Steph calls from the bedroom "Beany's all dressed, you can come in now."

I take a deep breath, grab my camera, and walk down the short hallway.

Stephanie airlifts an ever-immobile Beany from his bed while a younger, healthy version of himself watches from the step of his 15-ton truck.

Turning the corner I'm confronted by a wheelchair that looks more like a moon rover and a bed with a miniature crane attached to the ceiling. Steph stands to the left with the crane's controller in her hand and on the right wall is a large black and white photograph of a young, strong guy standing next to a massive truck. Lying on the bed is a small, frail man with hands like claws. He is dressed in a Canucks t-shirt, his head facing away from me, invisible eyes gazing out two large windows.

"Beany," Steph says, "this is Louis," motioning for me to come around the bed so that Beany can see me.

"Hi Beany," I say awkwardly.

His eyes dart from side to side before briefly pausing on my own.

"Hi," he says silently.

As a 25-year-old Donald "Beany" Johnson was, in most respects, a regular, hardworking young man. After "raising a little hell" through his teenage years he settled down with his high school sweetheart, Dale, got married and had a baby — a daughter named Tammy. He owned a successful business centred around a 15-ton dump truck and spent his time off with the newest member of the family. Then, one sunny Sunday in July, during a family outing to the countryside, Beany suffered a stroke.

After drifting in and out of a coma for more than three months, he awoke to find his body useless and his voice extinct. A prison of flesh surrounding a fully functioning mind, a mind incapable of communicating even the simplest request.

Beany and Stephanie's communication hinges on a simple system of letters and numbers laid out in grid. By blinking Beany can indicate a column and then a row slowly amassing words and sentences.

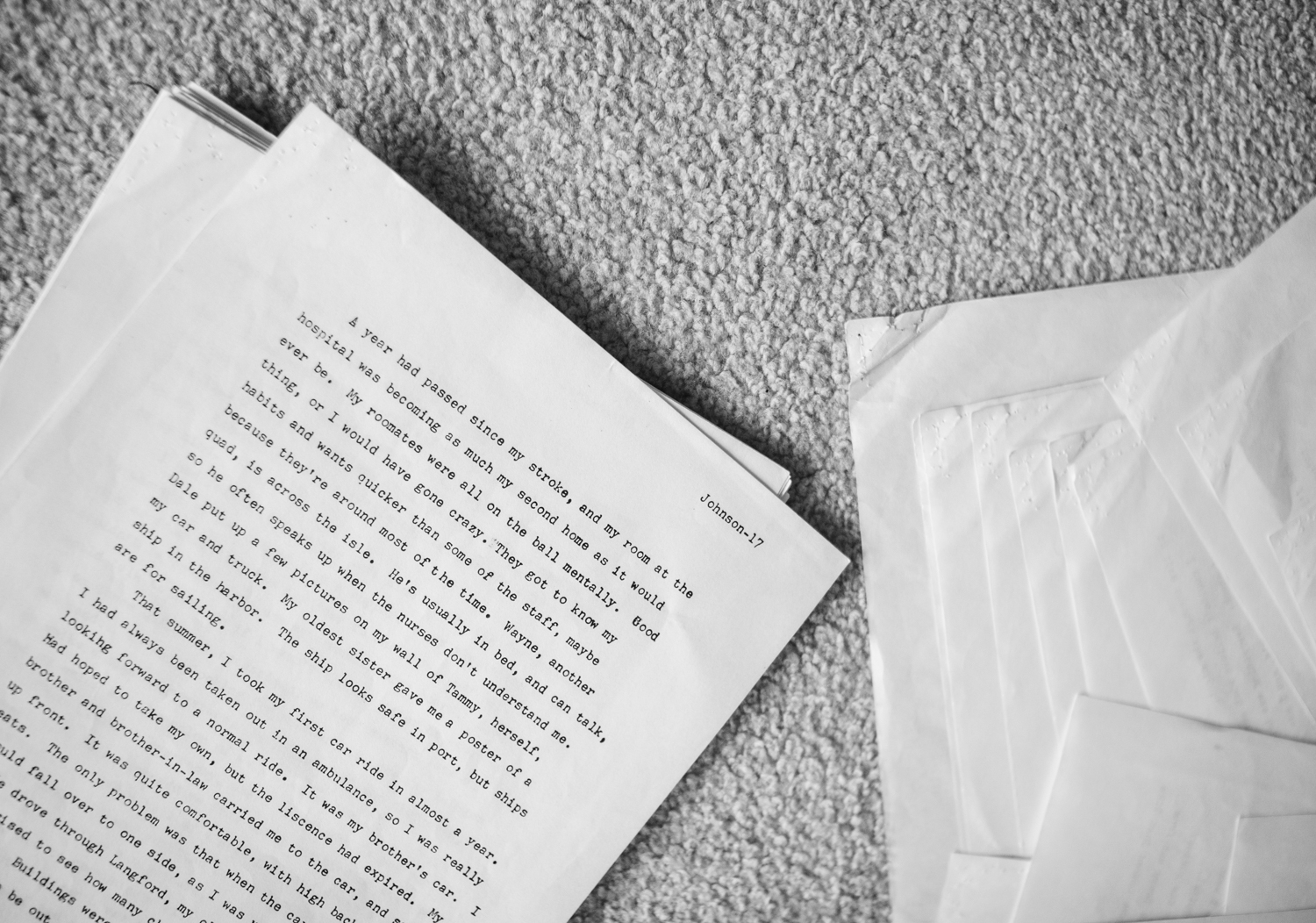

In a heart-wrenching 40-page manuscript, half of which was dictated to Dale through a system of communication involving the blinking out of individual letter — the same one that Stephanie uses today — Beany describes his life before and after the stroke. He talks of the ongoing frustration of nurses who view him as a job and not a person and people who assume that because his body is incapable, his mind must be the same.

"For anyone who may come in contact with a person who is non-verbal like myself," Beany writes, "remember to treat that person like a human being, regardless of your opinion or your perceptions."

As I read this I find myself struggling to grasp the life that burns within his body. It is difficult to believe that a person can live that long in such a state and still remain glowing, laughing, and joking. When asked what kind of music he likes Beany replies:

"Long live rock and roll and fuck disco!"

A page from Beany's manuscript that outlines his experience as a quadriplegic and the stroke that induced his fateful coma 25 years ago.

At first glance one might assume that Steph and Beany's six-year relationship has been a one-way street. One in which she bathes him, gets him dressed and combs his hair, before airlifting him into his wheelchair and making coffee and breakfast. And one that he, in return, gives nothing. This couldn't be farther from the truth.

"The most valuable lesson I have learned through Beany," says Steph, "is the choice we all have to be happy. Beany has lost all ability to move his body. He can't feed himself, roll over in bed or grab a snack when he's hungry. He can't talk on the phone to his daughter, or hug her, even if she were near. Yet somehow amidst these facts of his life, he has chosen to still be happy."

Beany was not always this upbeat however. There are parts in his manuscript that are clearly nothing more than therapeutic venting. In the second half, written more than 10 years after the first, by way of a Stephen Hawking-like system of Morse code beeped out with slight chin movements, he speaks of dark days spent staring out the windows of the Gorge Road Hospital with a rag-tag group of fellow wheelchair warriors.

"Marv is another cheery one, but his porch light flickers somewhat. I sometimes wish that mine was burnt out completely... 14 years of my sentence and still counting. How many more? Don't think that way Beany."

Two pivotal points came around the time that Beany wrote this. The first, was that after 14 years, Dale had had enough and filed for divorce. Beany could do nothing to make her stay and accepted this fact, although it clearly ripped him apart. The second was Beany's acquisition of the motorized wheelchair that he now owns today. It gave him not only the freedom of movement within the hospital but also the freedom to go outside and experience some of the everyday normalities that we take for granted. In his current apartment Beany can control the lights, TV, doors, and elevator — all thanks to his futuristic La-Z-Boy.

Beany and Stephanie share a laugh in his apartment outside Victoria, BC. Having spent so much time together they have developed an intuitive language all their own full of witty humour and compassion.

As we wait for the elevator Stephanie looks at me knowingly and emits the same waterfall laugh I had first heard bouncing down Beany's hallway.

"You look like your brain is really working something out," she says with a smile.

I pause, wondering how to best express the thoughts sprinting laps behind my eyes.

"I've never been so affected by someone who said so little," I finally reply.